Glacier Painting: Fathers, Sons & Misfortune

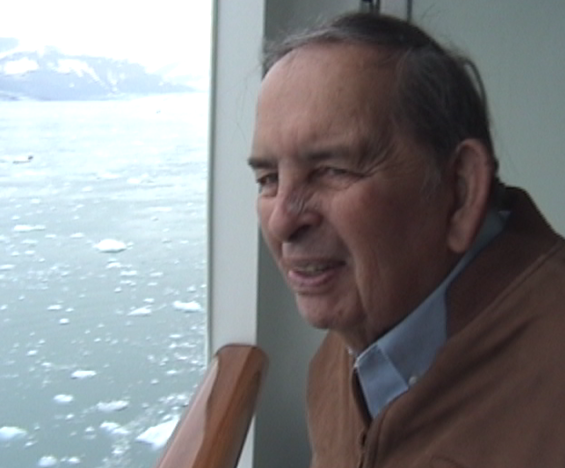

While recently looking through a 2002 photo album, a striking photograph fell out of the book. Taken from a cruise ship in the Alaska Passage during an ill-fated family vacation, I knew instantly that it could be used to create a powerful painting, especially on a large canvas:

The image viscerally called to me, at first because of its stunning beauty. Then I flashed on the helicopter trip with my sons, and the awe we felt landing and standing on Mendenhall Glacier. However, any thoughts I have about that trip are always punctuated by distress—but more about that later.

Melting Away

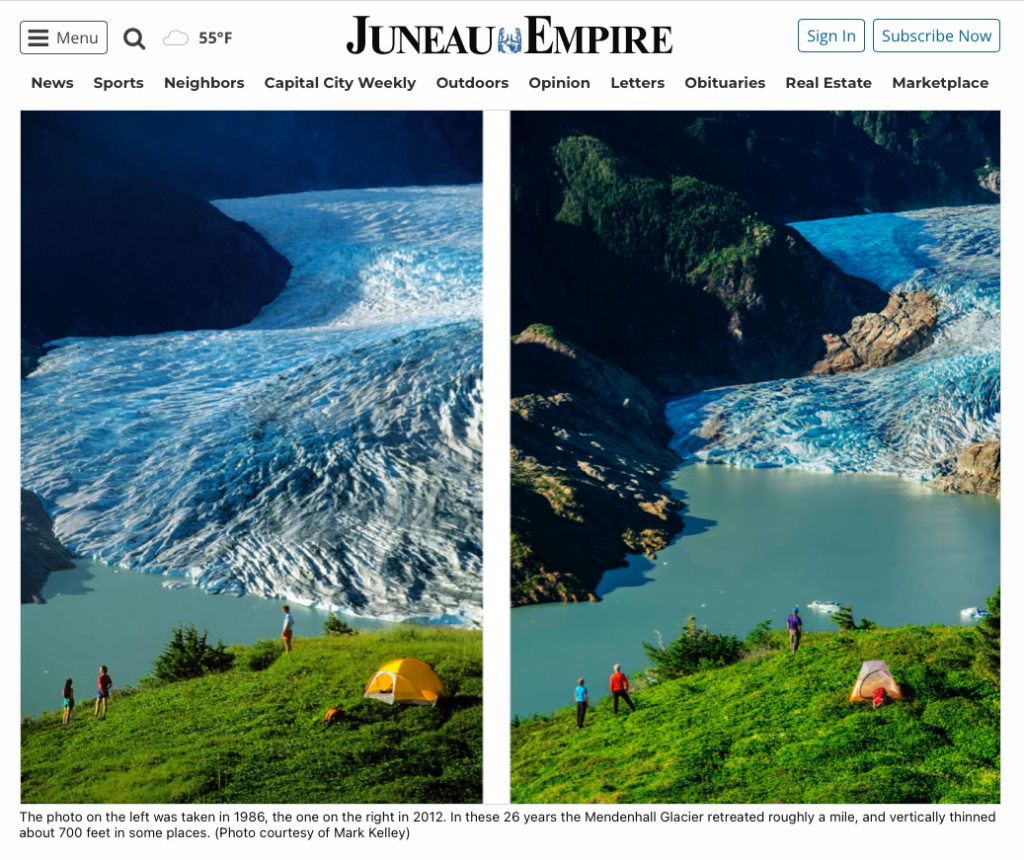

Of course, the picture also reminded me of the climate change crisis, the root of my fundraising efforts this year for the Ocean Conservancy. Located about 12 miles from Juneau, Mendenhall is one of the most visited and studied glaciers in the world. Therefore, it offers dramatic evidence of the increasing speed of glacial retreat. These comparison photos illustrate this point:

The “after” photo was taken a decade ago, however since then, glaciers are now melting 31% faster. About 13 miles long, Mendenhall shrank by about 2.5 miles over the past 500 years. But with its accelerated rate of retreat, it has lost nearly a half mile since I took this photo from the air:

How does glacial retreat effect us? The volume of globally melting ice is more than 328 billion tons annually—almost enough to put Florida under six feet of water every year! Over the next three decades, the East Coast will see a 10-14 inch rise in sea level and the Gulf Coast will face a 14-18 inch increase. Our glacier “air conditioners” are breaking down, resulting in warmer temperatures and more extreme weather events, like hurricanes. Okay, enough of my proselytizing…

Standing on Thin Ice

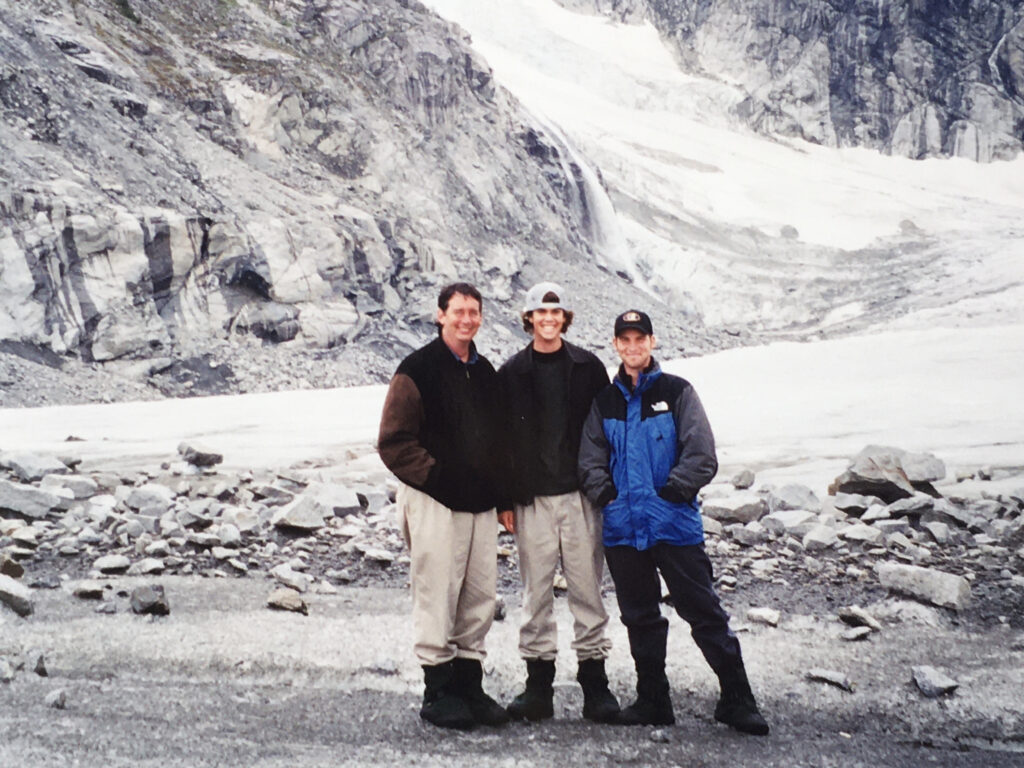

The helicopter trip to Mendenhall Glacier is a lifelong, bonding memory for me and my sons, Neil and Charlie. Once the rotator blades stopped spinning, we stepped out of the helicopter and onto the glacier. It wasn’t nearly as slippery as I expected it to be, and there was a profound silence—reverent and sacred. As those feelings sunk in, we became absolutely giddy to be there; and, I felt a special kind of paternal happiness from the shared experience. It was blissful, as appears obvious in the home video, the source of these images:

We’d seen a calving glacier from the ship, but we were safely standing near the base, where the ice was probably about 1,800 feet deep. However, there were noticeable areas of “blue ice” that we had to avoid. Of course, I liked the Cerulean blue tones, which I subtly included on the face of the glacier in both the painting above and this smaller study (both will be available in September):

Meet my Dad

The rest of the story has little to do with painting or conservancy and merely provides the context that led to the two Mendenhall paintings. Instead, I’m writing about fathers and sons.

The entire vacation to Alaska was a family gift from my dad, Melvin Cohn, who was 77 years old and had mellowed in the five years since my mother passed away. A volatile man, he could be fun loving and charming, as well as verbally abusive to his closest loved ones. Born in Chicago during the Depression, he came back from World War II and married his high school sweetheart, my mom. Their marriage endured his angry outbursts and her caustic responses, all of which obviously had an emotional impact on me and my sister, Ellen, who died at 46. Don’t get me wrong, my childhood was not a living hell—more like purgatory, because I never knew if Dad was going to be in a good mood or bad.

We were a close-knit family, even though he could suddenly go from enjoying dinner to unpredictably attacking any one of us—especially me once I became his primary caregiver. Nor were Lindsey and our sons immune from his rage. Yet, we followed the lead established by my mom, sister, and grandparents, who had coped with or avoided that side of his personality and loved him for his enduring qualities. I have many positive memories of happy times together, and those had an impact, as well.

After Mom died, I saw Dad frequently, and we talked on the phone about five times a day. He became much calmer for a few reasons, not the least of which was that I convinced his physician to prescribe him fluoxetine. I always assumed Dad would benefit from antidepressants, and they helped significantly. So, when he proposed taking our family on the cruise, we put our apprehensions aside and were excited.

Everything was going great on the trip, and the helicopter ride and time on the glacier were incredible! However, when I recently watched the home video, I noticed myself obnoxiously interrupting one son, as he tried to explain how he was going to photograph a scene. Instead of listening to him, I gave my opinion on how it should be done. I’m guilty of those kinds of annoying behaviors, and though it might not be as vicious as my dad’s conduct, I think all father and son relationships have some tensions. I’ve been on both sides of that equation, so I want to own up to my shortcomings and not just bash Mel.

Stranded

Anyway, after the helicopter ride, the boys and I returned to the ship, and they exuberantly told Lindsey all about it (also on video). Then, we went to Dad’s cabin and found him dazed. He had trouble speaking, couldn’t stand, and even to an untrained eye, it seemed like he had had a stroke. He was moved to the infirmary for observation and improved somewhat overnight. The next morning as we approached Sitka—our furthest destination north—I escorted Dad to shore on a small medical yacht and waved goodby to my wife and kids as we shoved off—reminiscent of the movie Titanic, when lifeboats were dwarfed by the towering ship that recedes into the distance.

On that first night at the local hospital, wired up to tubes and noticeably worried, he was uncharacteristically quiet. I looked out the window to see eagles in Sitka Spruce trees only yards away, and I thought about mortality. (Duh!) When I kissed Dad good night and said I’d see him in the morning, he looked at me with droopy eyes and gruffly mumbled, “Don’t let them bury me here!”

As tragedies go, this one could have been much worse. True, he had a stroke and we missed half of the cruise, but after a couple of days he was able to speak more clearly and walk with a cane. Obviously, there were no nonstop routes from Sitka to San Diego, and we needed four flights to get home. More than once we had to pass through security in those early days after 9/11, and he had to stand up from his wheelchair, remove his jacket, shoes, and belt, get patted down; and, I would have to put him back in order while juggling our carry-on bags.

By the end of that long and exhausting day of travel, I was at my wit’s end and couldn’t wait to get him squared away at home. Upon on arrival in San Diego, he desperately needed to use a restroom. But we were too late. I won’t repeat the entire outrageous situation—as I might to someone who was familiar with Dad’s colorful vulgarity—but, suffice to say that no adult son wants to be jammed into an airport toilet stall cleaning up his father’s messy butt and pants. Another bonding experience!

More than a Pretty Picture

The stroke had its effects and Dad never fully recovered. HIs health continued to decline, though he always remembered the cruise as a happy vacation with people he loved. We also got closer. By then, he regularly said that he was proud of me and “I love you.” Unfortunately, he missed my recognition as a painter. My father died peacefully two and a half years after my sons and I spent that remarkable afternoon on Mendenhall Glacier.

So, yes, these two paintings fit right into this year’s environmental themes, but they mean more to me. They represent memories and family relationships in good times and bad. In fact, most of my paintings have personal meanings: the exhilaration of watching our dog running on the beach in Morro Bay, profound appreciation of Balboa Park, Lindsey walking down steps at Monet’s garden in Giverny. I don’t generally know how people respond to my paintings, but I hope that the love I put into my artwork is at least conveyed in a few of them.

Coming Up Next

In September, I will be offering more than 20 paintings featuring the ocean, shorebirds, lagoons & ponds, unreleased Venice compositions, and the two Mendenhall Glacier paintings. The five-foot-wide one at the top of this article is pretty spectacular in person! Donations to raise funds for the Ocean Conservancy will be requested in exchange for artwork. Full details will be sent to my subscribers beforehand, so if you’re not on the list, sign up below!

References

Associated Press. “Satellites show world’s glaciers melting faster than ever.” April 28, 2021.

USDA Forest Service. “Mendenhall Glacier FAQs.”

Wikipedia. “Mendenhall Glacier.”

Leigh, I very much enjoyed your honest reflections about your relationship with your father and sons, and particularly your vulnerability about parental missteps; I can so relate. Thanks for sharing these and your magnificent northern landscapes!

All the best,

Dean

Leigh, what an emotional roller coaster ride the trip to Alaska was. Your powerful reflections on those experiences and your relationship with your dad make your art all the more interesting and beautiful.

Thank you for sharing. Steve and I miss you all.

Love and hugs, Shelly

Lesson learned: If you are old and have to travel, bring diapers!

Leigh, thank you for sharing those lovely stories; intertwined with much profound humanity and with your deep regard for grace. That painting reflects it all somehow.

With love, Ren

Leigh, that was an absolutely a beautiful and touching story. I respect your recognition of your dad in you, something you feel the need to change. When my folks passed you said, we’ll all orphans now. Thank you for the art, and it also seems dad came around at the end, saying he loves you is a beautiful thing.