My Year of Monet #5: Wives & Families

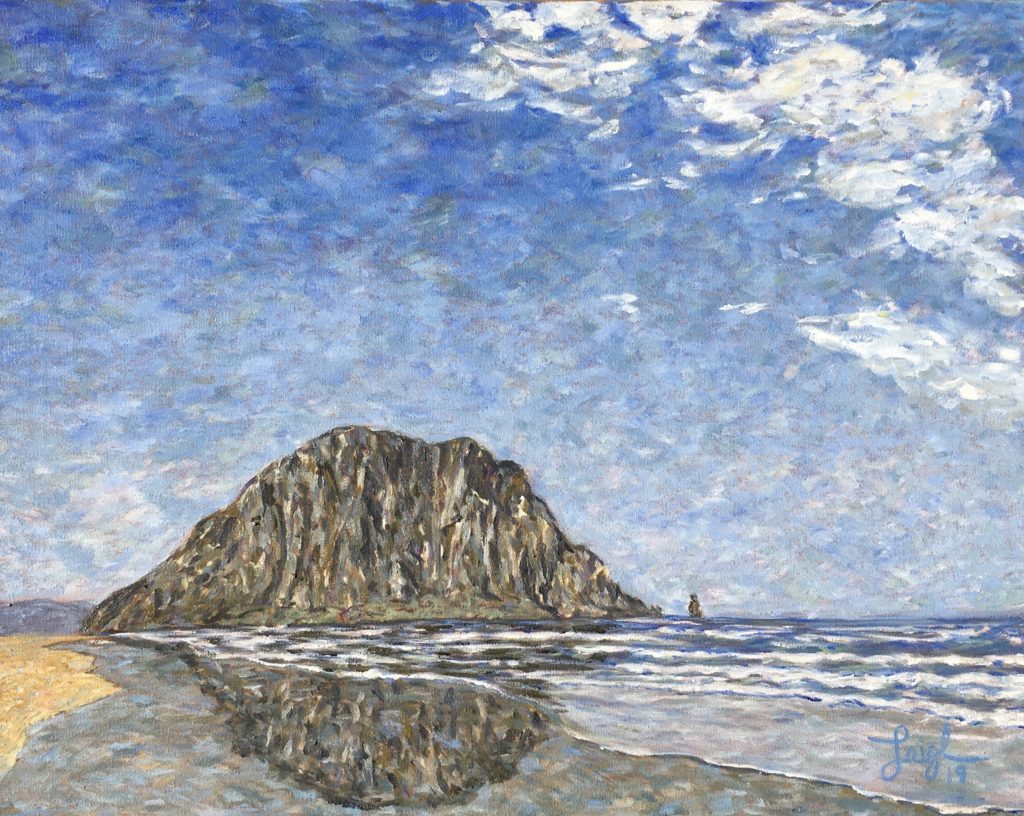

Featuring 2 of Leigh’s 2019 Paintings

In this post, I’m going to talk about Monet’s love life. As an aside, I hope you received my announcement about available paintings being offered until December 9, 2019. So far, I’ve received far more requests than paintings being offered, which has been exciting but disconcerting, because not everyone who wants one will get one. Two new paintings follow, but they aren’t available:

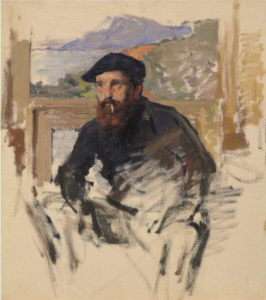

What’s his name?

There’s disagreement among many popular websites and some books whether he was named Claude-Oscar or Oscar-Claude. His earliest few paintings are signed “O. Monet” but he changed that to “C. Monet” soon after. From the time he was 25 years old, he signed “Claude Monet.” As an adult, he was “Monet” to everyone.

Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s talk about love. During “My Year of Monet” I’ve learned about more than just his painting techniques. Monet’s personal life intrigued me, his character, how he treated other people, his family life. The more I read, the better I understood him; but, I also, continuously, reflected on the parallels between our lives—just as I have done with our paintings. So, I’ll share a bit more of myself once I’ve told you a little about him.

Love of his Life #1

Not much is mentioned about Monet’s romantic life until he met a 19-year-old Parisian girl, Camille-Léonie Doncieux in 1865. He was 24 at the time, and for the next 14 years she modeled for him in more than 30 paintings, sometimes appearing as multiple figures. Camille quickly moved out of her family home and into his. A few months later, they fled in the night to escape past due bills; and, then repeated the process elsewhere! (Roe, p. 39)

In 1866, he painted her larger than life in The Woman with a Green Dress, and the following year she gave birth to their son, Jean Armand-Claude Monet, which he described in a letter:

“I didn’t have enough money to stay in Paris while Camille was in labor…She’s given birth to a big and beautiful boy, and I don’t know how, but I feel that I love him. And it pains me to think of his mother with nothing to eat…Now, she and I are totally without money.”

The birth certificate indicated that Jean was, “the legitimate son of Claude-Oscar Monet and Camille-Léonie Doncieux, his wife,” which was untrue. Because Monet’s father disapproved, they didn’t legally marry until 1870.

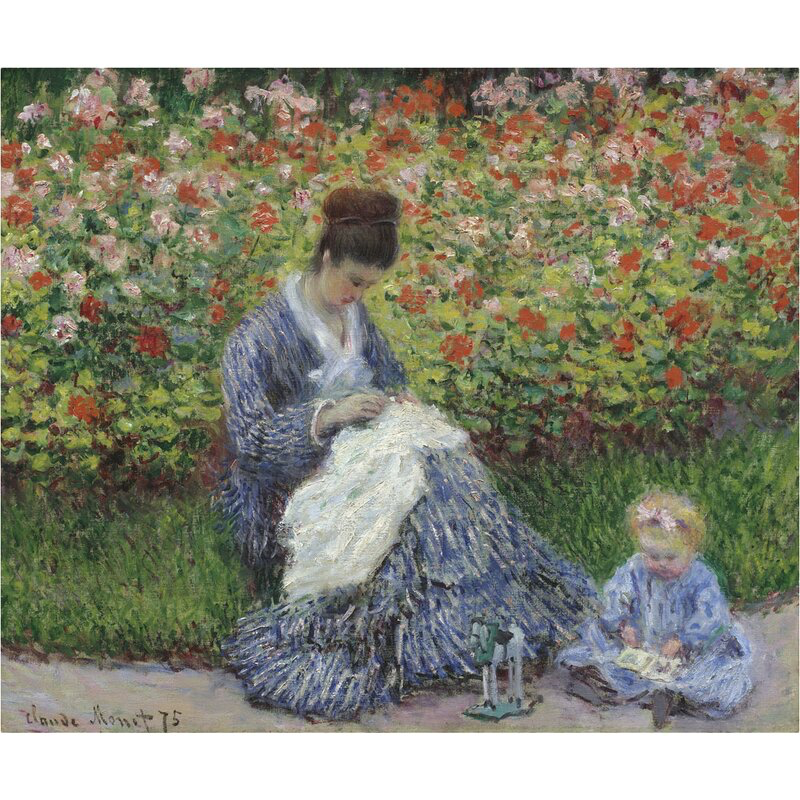

Monet became enormously productive in the following years, which included the initial Impressionist exhibitions, and the family moved to the port of Argenteuil. This period was the height of Impressionism, in which he painted some of his loveliest landscapes and pictures of mother and child. Nonetheless, finances were tough—even Camille did not receive much of a family inheritance that had been owed to her.

Decades would pass before Monet stopped spending more than he earned. Throughout his marriage to Camille, paintings were selling, but not with the frequency he had hoped. In 1876, he wrote:

“The creditors are proving impossible to deal with, and short of a sudden appearance on the scene of wealthy art patrons, we’re going to be turned out of this dear little house, where I led a simple life and was able to work so well. I do not know what will become of us. I had so much fire in me, so many plans.”

However, his words proved to be prescient when soon after a department store tycoon, Ernest Hoschedé, commissioned Monet to paint large, decorative pieces at his estate.

Camille, who was feeling ill, did not accompany him….

Love of his Life #2

While Hoschedé went off to Paris to address a financial crisis, Monet remained painting, alone with the businessman’s wife, Alice. Nine months later, she gave birth to the last of her six children. Eighty-three years later, Jean-Pierre Hoschedé released a two-volume biography about Monet and life in Giverny. He plainly resembled the painter, and implied in the book that he considered himself to be Monet’s son. (Wildenstein, p. 125)

By 1878, everyone’s finances were in peril, and a weakened Camille gave birth to a second son, Michel: “My wife has just had another baby and I find myself penniless and unable to pay for the medical care that mother and child must have.”

At the time, they were living in a Paris apartment using money borrowed from the painters Edouard Manet and Gustave Caillebotte. When this arrangement could not be sustained, Monet and the Hoschedé families (twelve people plus servants, tutors, a nurse, and a cook) moved into a small house in Vétheuil together [which I blogged about last time]. Alice attended to Camille, whose health was worsening, and eventually Ernest and the employees left—except for the cook. Monet wrote to a friend, “I can’t bear to see her suffering like this and not be able to give her any relief.” (Roe, p. 196)

After months of deteriorating with uterine cancer* that had spread, Camille died at the age of 32, her grieving husband and his future wife at her bedside. Not to minimize Monet’s loss, he was deeply effected by her passing and famously painted her and wrote:

“Watching her tragic forehead, almost mechanically observing the colors which death was imposing on her rigid face. Blue, yellow, grey, what do I know? How natural to want to reproduce the last image of her, who was leaving forever. But even before the idea came to me to record her beloved features, something in me automatically responded to the shocks of color. I just seemed to be compelled in an unconscious activity, the one I engage in every day, like an animal turning in its mill.” (Roe, p. 209)

Oh, Jealous Lover

Although Alice and her daughters attended to Camille conscientiously until her death, she wasted no time asserting her dominance over Monet. She started by ordering him to destroy all of Camille’s letters!

She expected him to write to her daily when they were apart, and his letters were affectionate and clearly show that he loved her. During one separation, “Must I learn to live without you?” Nonetheless, she remained married, albeit estranged from her husband. Periodically, Ernest would visit their home, and typically, Monet would depart. From Etretat in 1883 he encouraged her to confront the dilemma:

“It makes me miserable to know you are unhappy…The longer it drags on, the harder it will be. There must be a way of drawing him (Ernest) out and have a serious and reasonable discussion. As for me, have no doubts, I think of you constantly. You can be sure of my love. Be brave.”

Alice insisted that her letters to him be destroyed after they were read, but fortunately she kept all of his for posterity. One wonders how Monet’s love for Camille was expressed in writing, but we only have his paintings, which clearly show how enthralled he was by her.

Unlike his good friend Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Monet didn’t paint nudes. When he once proposed bringing a model back from an excursion, Alice told him that he would have no home or family to come back to if he brought a model to their house. So, he stuck with her daughters, especially Suzanne Hoschedé (below right), who bore a resemblance to his late wife (left):

Even though Alice was controlling and apparently conflicted, I don’t want to portray her as a villain. An intelligent woman from an aristocratic background, she pushed Monet to be successful and called upon her contacts to promote his work. She ran their household of eight children, and attended to Monet’s temperamental needs.

All in the Family

The Monet household with eight children were a mixed-family if ever there was one. Can you imagine sitting down to dinner with this group?

When they moved to Giverny in 1883, there were only 300 residents of the village. However, a couple of years later when an artist’s colony sprouted up, Monet mainly stayed secluded. He was a celebrity and guarded his privacy from the wannabes peeking at him through the bushes. However, the children mixed more freely with the newcomers, and Monet and Alice had to fight off the suitors. In 1892, Monet lost his favorite model, Suzanne, when she married American painter and photographer, Theodore Earl Butler. Slightly before the wedding, Monet and Alice wed in a civil ceremony out of a sense of propriety.

Five years later, Jean married his step-sister, Blanche, and Monet lost his assistant, the only child who painted. Soon after, Suzanne tragically died at the age of 31, leaving the care of her two children to her sister, Marthe, whom Butler married the next year. As far as I can determine in my research, Monet has no surviving descendants.

On May 18, 1911, he wrote to his art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, “I have some very sad news for you. My beloved wife is about to die, it is only a matter of hours now. I can’t tell you what I’ve been going through…my strength and courage are giving out. “

Upon her death, Monet was heartbroken and stopped painting entirely for two years. The grown children that remained in the area (and staff) attended to him; and, when his eldest son died in 1914, Blanche moved back home. For the final 12 years of Monet’s life, his stepdaughter/daughter-in-law cared for him, assisted when he painted, and deeply loved him.

Georges Clemenceau adored Blanche and wrote, “She was admirable in every way. She took care of him, pampered him. She watched over him as if he had been her child.” He called her “saintly” and believed that without her support, Monet could not have painted the Grande Décoration murals, which hang in the Musée de l’Orangerie. (King, P. 297)

Different Strokes

Monet’s were two entirely different kinds of marriages. Camille was much younger than Monet—a girl, really—and he obviously was captivated by her beauty. Probably for sentimental reasons, he kept the massive Women in the Garden (below left) in his studio until he was 81 years old, a painting in which Camille appears three times (white dresses). They were together for 14 years and married for nine, practically all of which were spent in poverty.

On the other hand, Alice was closer in age—late forties—and the mother of six children, when they began cohabiting. As far as I can tell, although she modeled for John Singer Sargent, Monet may have only (purportedly) painted her once, in Meadow at Limetz (below right with parasol). Despite Wildenstein’s supposition that it might be her, I think it is more likely Alice’s oldest daughter, Marthe, who is watching Jean and Michel. Monet relied on Alice logistically and emotionally, and they were married for 19 years.

Painting Inspiration, yes. Role Model, uhh?

I’ve written repeatedly about “emulating” Monet and “aspiring to paint” like him. On the other hand, I would not want to be like him! Monet was a 5’5″ gourmet who liked fine wine. I’m a six-foot pescatarian who rarely drinks. Although my wife, Lindsey, and I struggled financially for many years, we never skipped town without paying our rent or left a bill unpaid. Monet was often self-absorbed, depressed, and irritable. Filled with self-criticism, he was a larger-than-life, egocentric figure. I’m a generally easy going, self-loving, empathic person who spent a career trying to help people. More to the point, Lindsey and I have been in love and happily married for 42 years (thus far)—much longer than both of Monet’s marriages combined. No, I’m glad my life is nothing like his. But, would I trade my life of contentment and service for his talent? Absolutely not!

Upcoming in “My Year of Monet #6”

The final installment about Monet will review “Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature” at the Denver Art Museum. This exhibit has 120 paintings from throughout his career and is the largest U.S. Monet show in more than twenty years. I’ll also look back at my “Year of Monet” to summarize my insights. In the meantime, take a look at the paintings I’m offering to give away until December 9th.

References

* Various causes of Camille’s death are in the literature, but uterine cancer is the most likely. Unfortunately, my mother also died from complications of the same disease. I can personally attest to the months of pain she endured and how draining it was for our small family as we cared for her throughout the illness.

Unless otherwise noted, Monet’s quotes in this article came from letters to friends and Alice. They were taken from the wonderful video, Exhibition on Screen: I, Claude Monet, Seventh Art Productions, Brighton, UK, ©2017.

King, Ross, (2016) Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies, Bloomsbury, New York.

Roe, Sue, (2006) The Private Lives of the Impressionists, HarperCollins, New York.

Wildenstein, Daniel. (1996) Monet or The Triumph of Impressionism, Taschen edition.

I concur that you have had a better life: more stable, less privations, better dogs-Cozy, not to forget

Alice, and a most wonderful wife.

[…] of my blog on Monet’s “Wives and Families” will remember, his second wife, Alice. They spent two and a half months in Venice, their last trip […]

Thanks Leigh for the blogs. I enjoy reading and learning about The artist’s life.

Thank you, Leigh. Your blog is fascinating and a pleasure to read. C.

Hi Leigh,

I enjoyed reading your blog very much. I think of you and Lindsey often and love it that you are pursuing your passions and sharing with us! I hope all is well with your family.

My best,

Bonnie

Nicely done! I really enjoyed reading this.