My Year of Monet #4: His Earlier Paintings Influenced Mine

Featuring 4 of Leigh’s 2019 Paintings

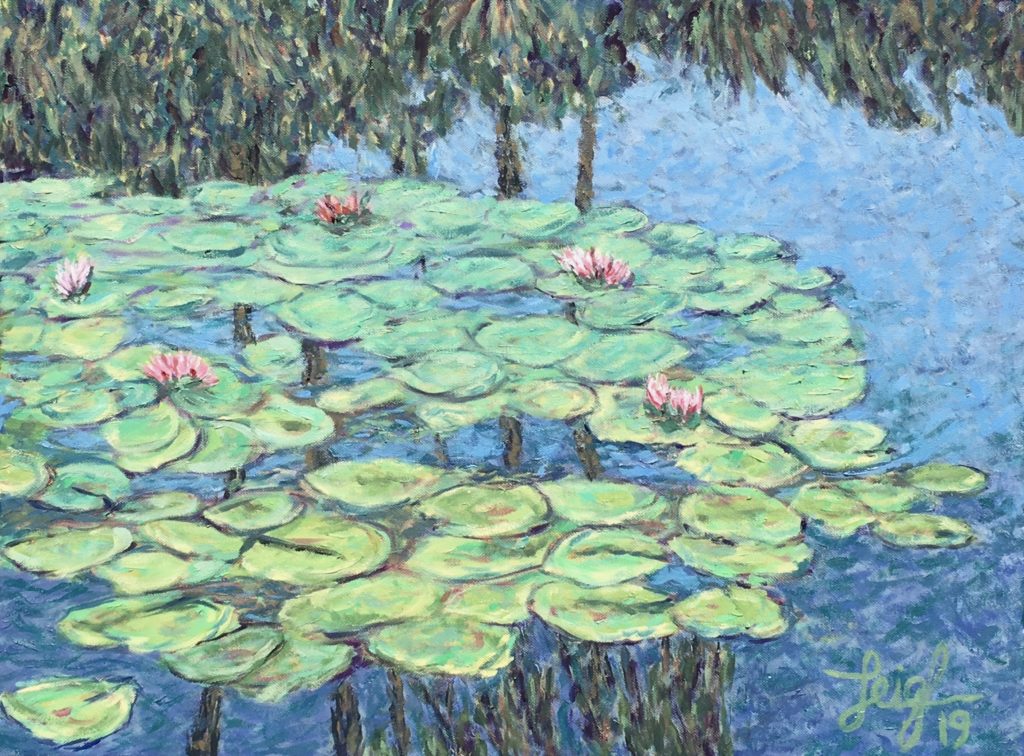

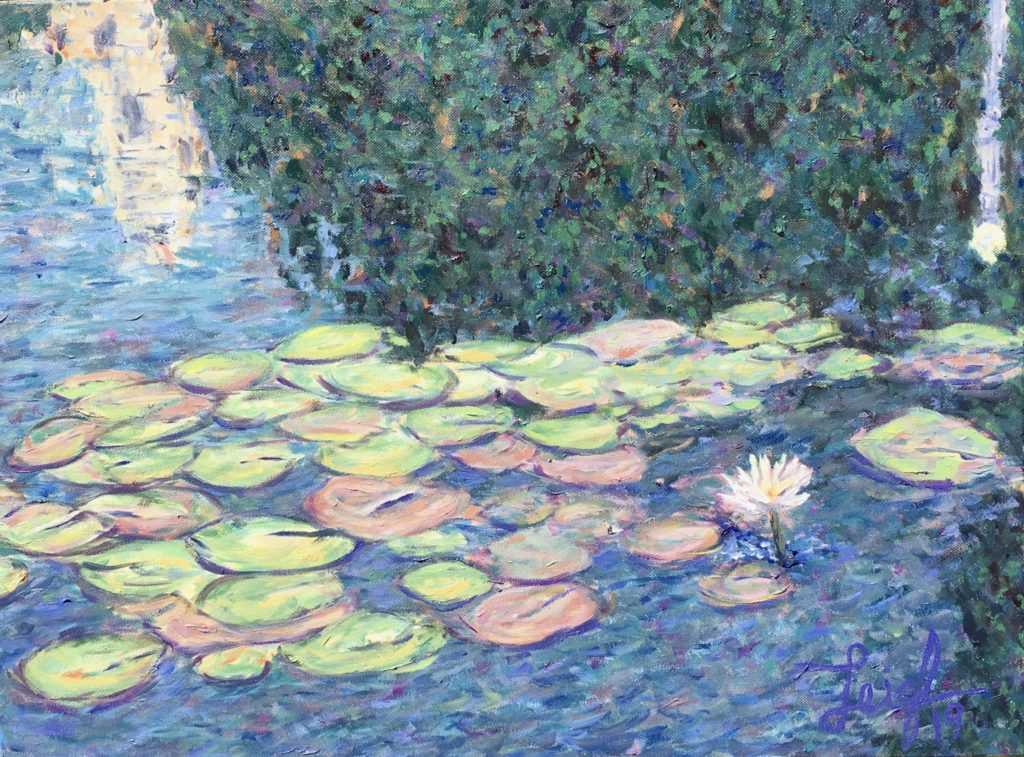

After completing the “Paint Like Monet” project (see my last blog article), I painted four more water lilies. For these, I switched up colors and felt looser and freer than I had while concentrating so hard on Monet’s techniques. I returned to the Balboa Park lily pond for a new round of photographs, and they served as my source. These pictures are unrelated to the topic of this current article, but I wanted to share them with readers anyway. Incidentally, in mid-November I plan to offer to give away at least 20 paintings, including some of these:

Making a Statement

Claude Monet made conscious decisions about the subject matter of his paintings, and my “Year of Monet” led me to revisit my own decision making process. I’m a self-trained painter, which means that instead of taking classes, I studied on my own—talking to painters about their practices, reading books, and trying to figure out how the artwork I liked was created. No one suggested what I should paint. However, in looking back, I was struck by some similarities of my own works to Monet’s that I had never before noticed.

Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Morisot and the other Impressionists individual approaches varied, but they were all purposefully breaking away from convention. These younger, avant-garde artists’ use of plein-air, brighter colors, dappled brushstrokes, and depiction of modernity set them apart from the bucolic style of their predecessors (Corot, Daubigny, Millet, etc.)— the leading landscape painters of the mid-1800s. For example, Edgar Degas eschewed the portrayal of models as lovely, and instead showed them in mundane, behind the scenes studies of homely ballet dancers dealing with sore feet and demanding music tutors.

Compare these canvases painted around the same time by the establishment artist, Corot, and Impressionist, Pissarro:

When you enlarge them, you can see that Corot’s peaceful, idyllic scene is created with warmer colors, finer brushstrokes, and attention to detail. Pissarro’s was painted quicker, with dabs of color and implied shapes as the landscape recedes. It’s a hot day for Pissarro’s hard workers (despite cooler colors), especially compared to Cortot’s woman sitting peacefully while the cows graze.

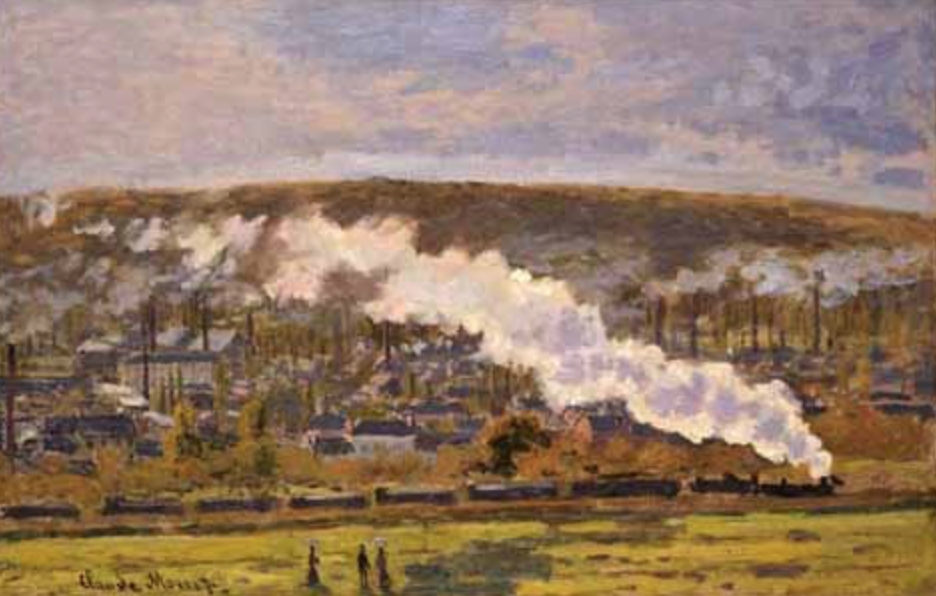

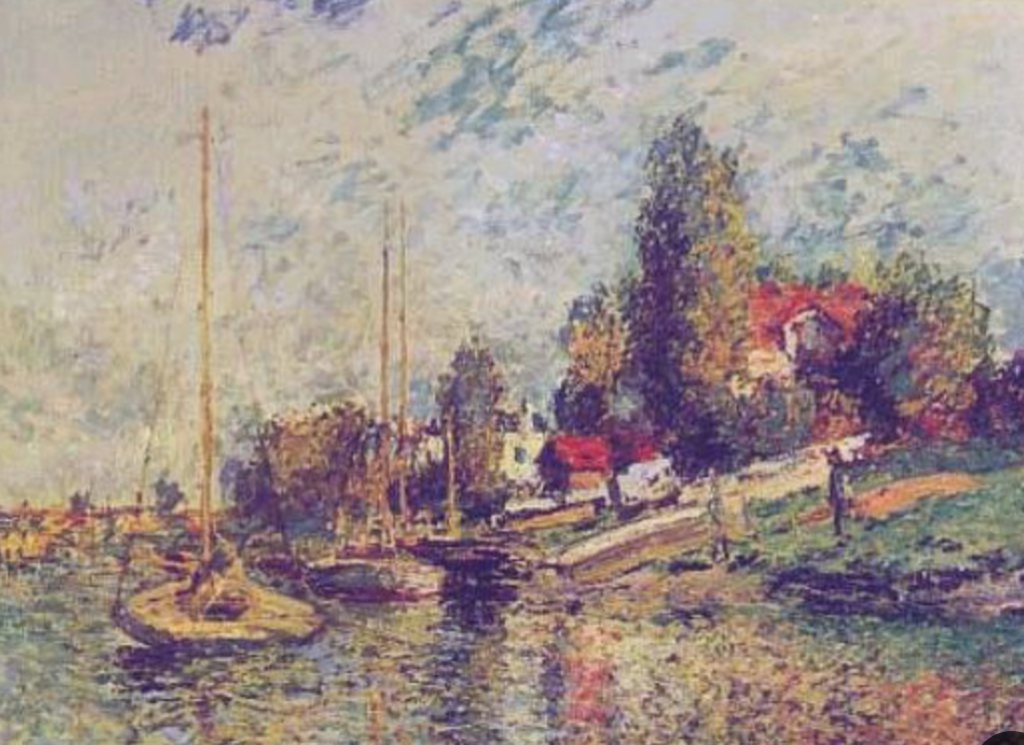

France in the early 1870s was undergoing reconstruction after the end of the Franco-Prussian War; and, by combining nature and contemporary, utilitarian objects, Monet depicted changes to the countryside. In addition to documenting the new landscape, he was also being subtly subversive as opposed to the art establishment. He painted the beauteous Seine, but also included steel trestles, which were generally considered as hideous assaults on gentility. A sail boat regatta includes humble fishing crafts in the same scene. A smoke-billowing train races along in front of a hillside crammed with factories:

These are not necessarily his most iconic canvases—the ones everyone regards as beautiful—but are important examples of how he was pushing the envelope in new and revolutionary ways.

Conscious, Unconscious, or Subconscious?

Over the past half-century, I’ve looked at hundreds of Monet paintings, but primarily focused on his brushstrokes and color. “My Year of Monet” compelled me to dig deeper, and I discovered more about his content. When I created many of the compositions I’ll share in this blog article, I thought I was acting independently and without direct influence from Monet, but now I’m not so sure. Compare these three paintings of mine to the ones of his above (please click on them):

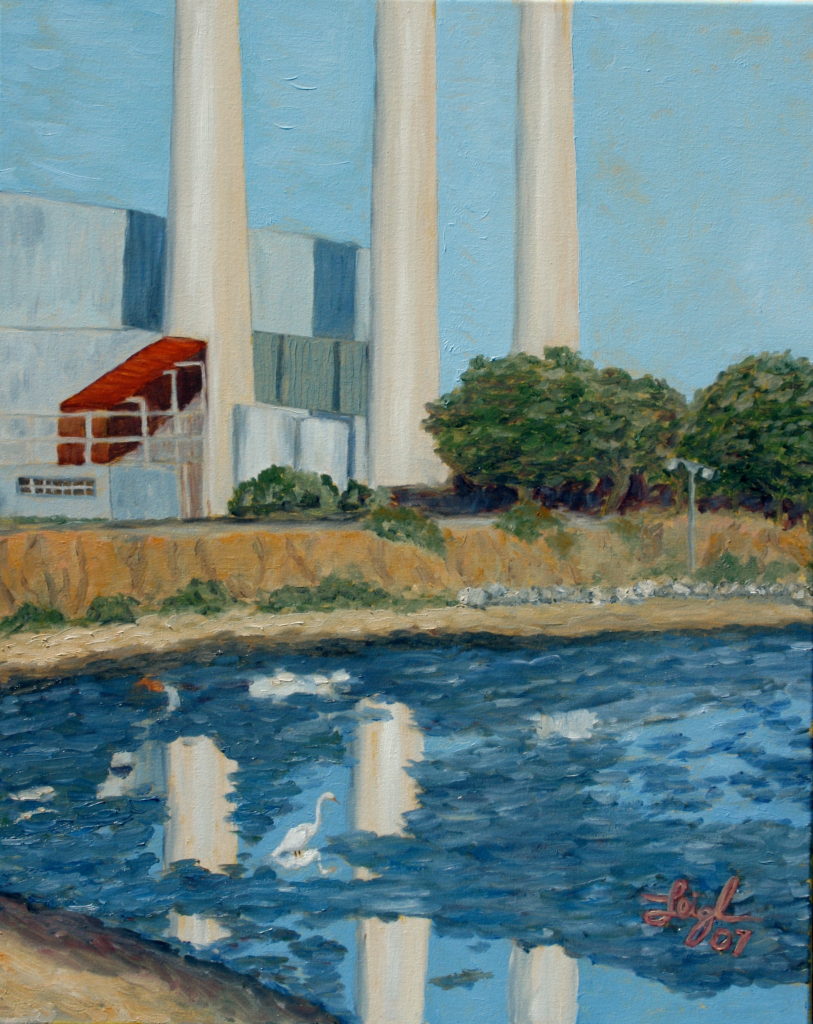

Morro Bay Power Plant ~ Neil Cohn, Boston, MA 2007 • 24 x 30

The Boat Race (In Memory of Jan Nathan) ~ 2007 • 48 x 24 Terry Nathan, IBPA • Hermosa Beach, CA

Coaster over Agua Hedionda ~ Howard Anton Duncan, Oceanside, CA 2013 • 30 x 10

In the first picture, I made a conscious decision to contrast this Morro Bay power plant’s powerful smokestacks (like Monet’s bridge columns!) with the elegant egret in the foreground—a statement about technology encroaching on nature. In my mostly monochromatic boat race, a dark red was inserted to symbolize a deceased friend rather than depicting leisurely boaters. I included the Coaster train on the right canvas to provide a sense of location and movement (anyone from Carlsbad would recognize the site and commuter train), though without the clouds of smoke that dominated his canvas. In each of these paintings, I attempted to go behind “pretty picture” to make some kind of comment, but unlike the Impressionists, I was not trying to upend the art world as we know it.

Fascinating to me in retrospect is how much Monet’s work inspired so many of my compositions, even though I was not aware of the connection when I painted them. I may or may not have seen his related scenes, but in most cases was not thinking of them while I created mine. Whether there was a subconscious connection, I cannot say. Let’s look at some more examples…

Paul Hayes Tucker’s book, Claude Monet: Life and Art (1) opened my eyes to many of the Monet selections I’m using in this article, and he refers to “Landscape with Factories” as a “surprise,” and it sure surprised me to see his smokestack used in such a similarly key way as in my lagoon view (right). Painted when Monet was 18 or 19 years old, this is one of his earliest paintings—catalogued #5 (2)—and I definitely had not seen it prior to my 1999 phase of power plant studies. At the time, I—like him—was just getting started with painting and selected this theme because the power plant was an easy structure to draw and I liked juxtaposition of it against the lagoon and ocean. According to Tucker, Monet had a greater purpose:

“Everything about this painting is different from the bucolic image of a sun-drenched place untouched by time and change…here is a landscape altered by the gritty world of industry and work…Monet did not simply focus on the seductive beauties of the rural sites surrounding his home. Instead, even at the early stage of his career, he also trained his eye on rawer, more challenging subjects…which were distinctly a part of his contemporary moment.” (3)

Likewise, I was unfamiliar with Monet’s Boats in Argenteuil (below left) when I did this early plein-air of boats in Morro Bay—a rare, pre-Projector Technique painting of mine:

Vétheuil

In 1878, Monet moved to the picturesque village of Vétheuil, just over an hour northeast of Paris on the Seine. Along with his ailing wife, Camille, and their two children, he moved into a house with Alice Hoschedé (his future wife, who was estranged from her husband, a bankrupt art investor) and her six children. Suddenly, he was the head of a large household. Even though he had achieved notoriety during this period of the Impressionist Exhibitions (1874-1886), the value of his paintings had plummeted after Ernest Hoschedé’s collection was auctioned off at reduced prices. Monet had to borrow rent money and aggressively market his artwork. Working under pressure, he produced some of his most gorgeous, iconic works in those years. In a letter after the move, he wrote, “I have set up shop on the banks of the Seine at Vétheuil in a ravishing spot.” (4)

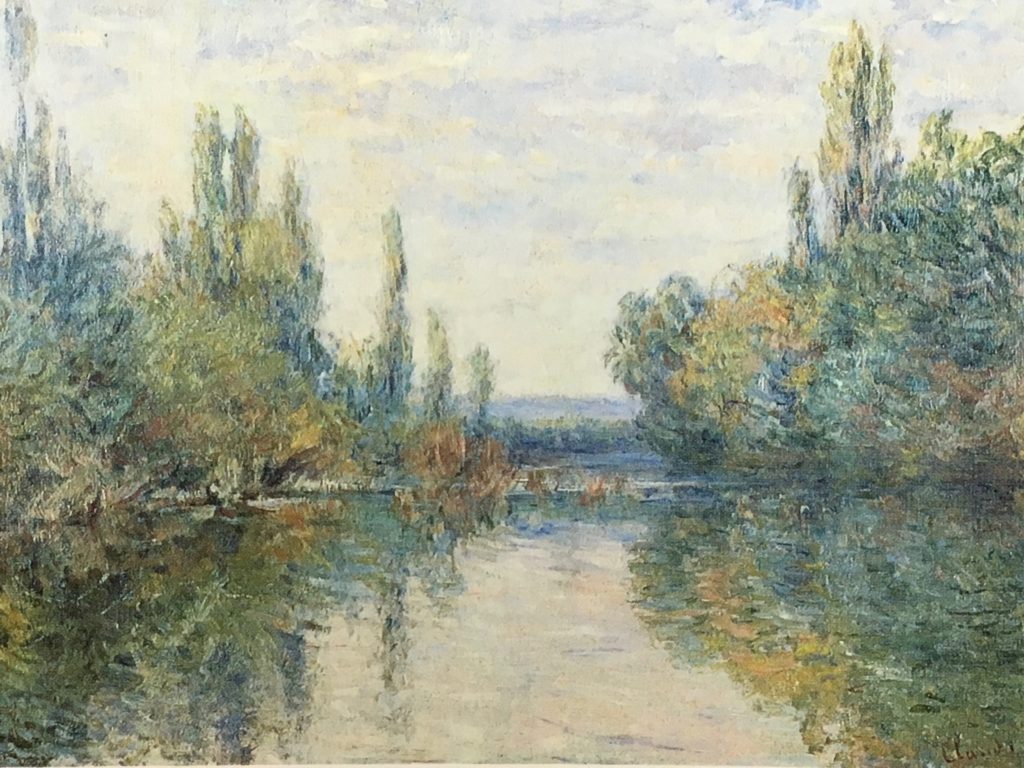

Monet: An Arm of the Seine near Vétheuil – 1878

On the Swan River #1 ~ Steve and Gerry Connolly, Big Fork, MT 2009 • 24 x 18

Monet completed several paintings from the same vantage point as “An Arm of the Seine near Vétheuil” in 1878; and, when I recently looked at them, I was struck by how much they resembled my Swan River series. Like him, I had come upon a scene that was so captivating that I painted it over and over. Again, my intentions at the time had nothing to do with replicating his pictures, but there’s no question that the Seine compositions must have had an influence on me.

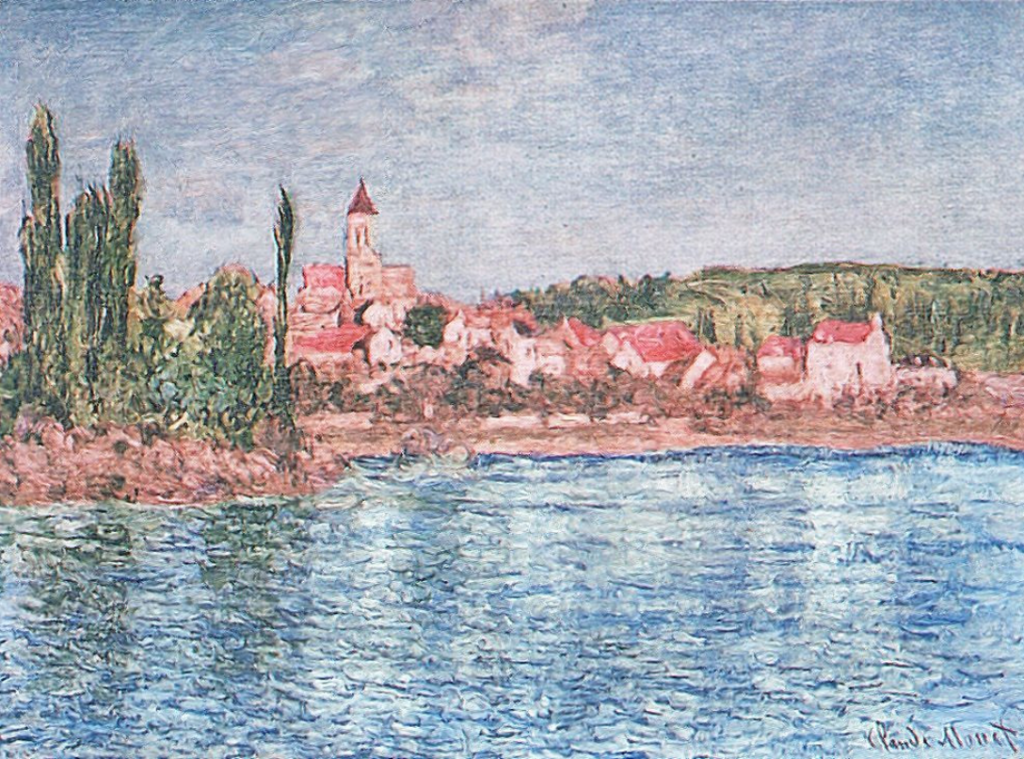

I also, obviously, have been attracted to similar perspectives, such as in these shorelines:

Monet: The Seine at Vétheuil – 1880

Santa Barbara #1 ~ Steve & Shelly Koski, Santa Barbara, CA 2003 • 24 x 18

Obviously Influenced

Monet spent his formative years near La Havre, a port on the Normandy coast, and in the early 1880s, after Camille’s death and before moving to Giverny, he often returned. Although they were not yet married, he and Alice cohabited along with the eight children, so I assume he needed to get away from time to time! In 1883, he went to the town of Étretat, a little further up the coast, where he painted a variety of seascapes, including a couple of The Manneporte. Those paintings guided me when my brother-in-law, Ben Hall, shared a photo he took while kayaking in Puget Sound:

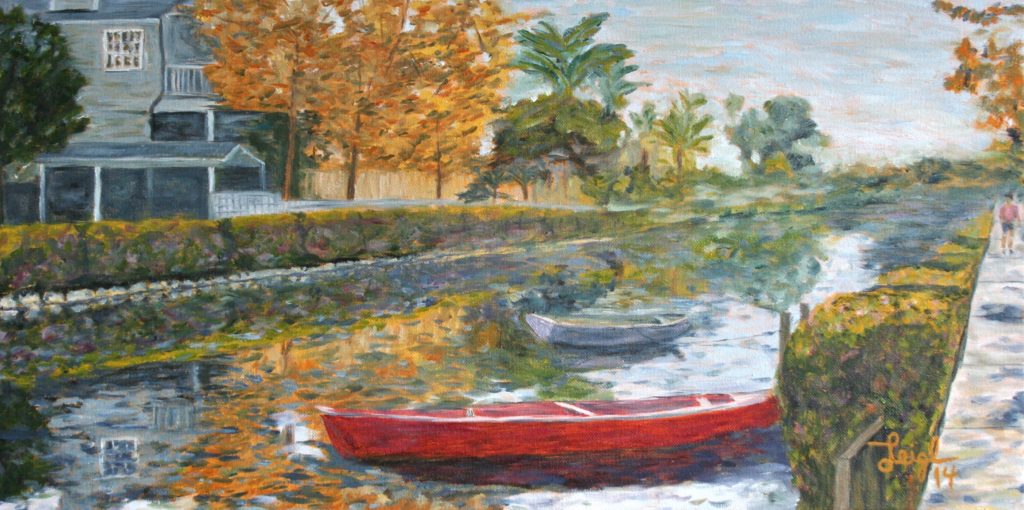

I also used red to highlight boats in certain pictures, like he did:

Red Canoe in Maine ~ Auction for PAVE, Tacoma, WA 2010 • 30 x 24

Venice, CA Canal #2 ~ Steve Emmett, Providence, RI 2014 • 20 x 16

Venice, CA Canal #3 ~ Bonnie Hall, Carlsbad, CA 2014 • 24 x 12

Monet: Red Boats, Argenteuil – 1875

Monet’s Rouen Cathedral series influenced my approach to the facade of the San Diego Museum of Art in this detail below:

Emulate not Imitate

Only someone with less talent can try to emulate another’s greatness, and if you look at the pictures in this article, there’s no question about who is the master and who is the hobbyist. When people say, “Oh, you paint like Monet,” it is a tremendous compliment, and I’m really not worthy of such comparisons. But, I think what they are noticing is commonality in brushstrokes, color, and subject matter. Regardless, I am trying to develop my own techniques, style, and voice.

Upcoming in “My Year of Monet”

I’m in the early planning stages of the final two installments in “My Year of Monet,” which will present fun, somewhat rare, facts about Monet (and probably some about me) and a December recap of my visit to the Denver retrospective show, “Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature.”

Also, in mid-November, I plan to announce a give away of more than 20 paintings, so stay tuned…

References

(1) Tucker, Paul Hayes, (1995) Claude Monet: Life and Art, Yale University Press, New Haven.

(2) Wildenstein, Daniel. (1996) Monet: Catalogue Raisonné – Werkverzeichnis (Volumes II-IV), Taschen edition.

(3) Tucker, p.12.

(4) Wildenstein, Daniel. (1996) Monet or The Triumph of Impressionism, Taschen edition, p. 137.

[…] people plus servants, tutors, a nurse, and a cook) moved into a small house in Vétheuil together [which I blogged about last time]. Alice attended to Camille, whose health was worsening, and eventually Ernest and the employees […]

Leigh, I always enjoy reading about your artistic process (conscious and other less attendant ones.) Your paintings have enriched us all. Happy 70th to Lindsey and Cozy…they don’t look it!

Hey Lee:

Really enjoyed the history of Monet and how his work broke with convention. I also love your work and I think you are a bit beyond a hobbyist at this point. Keep up the good works.

Leigh, how wonderful to see these paintings—both yours and Monet’s. I am a Monet freak, chasing his paintings all over Paris galleries and Giverny. I love the facts in this blog. I would love to own one of your paintings. It would be an honor and remembrance of two dear friends! Happy Birthday, Lindsey 💜💜💜. I think of you every time I look at my Rock Star baby.

Well, Leigh, you have some wonderful years of study, research, and painting under your talented brush. I look at my own and see way too much “fussing” over my painting. I just cant leave it alone. You just portray your feelings and objectives with style and freedom. I would not know where to begin painting like that, but I love the peace I see in your drawings and paintings and appreciate being able to see them and learn as well. Thank you for including me in your newsletter.

Wow! I really see your work maturing Leigh. “Hobbyist” is WAY too humble (in my humble opinion…) Beautiful paintings. Love to you folks. Always, S.

I’m so loving going through this process and so touched by your talent and sentiment. I’ve always been a fan of a few special impressionists, Monet being high up on the list. And I’m a big fan of yours. I’d love another painting but I don’t want to be a glutton so perhaps you can let me know if there’s one somewhere for me after others who don’t own one choose. I’d trade you for one of my watercolors!