My Year of Monet #2: Painting with Monet’s Techniques

Featuring 2 of Leigh’s 2019 Paintings

Monet Painting Sells for WHAT?!

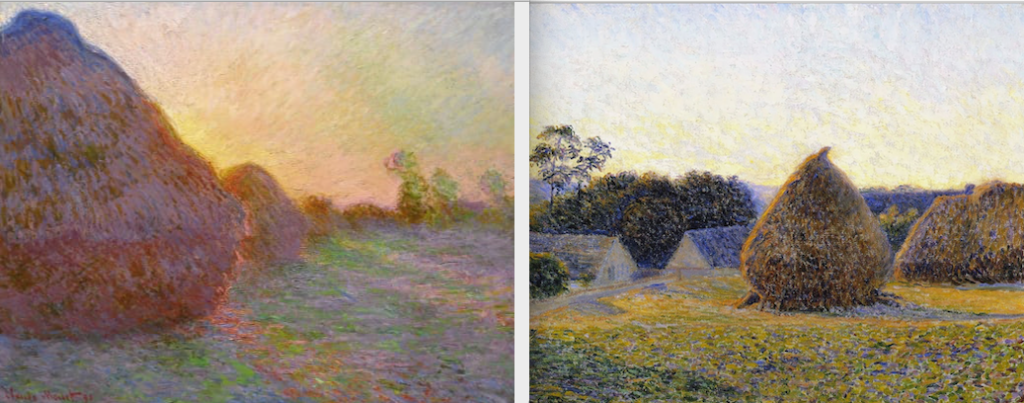

Before I describe my use of his techniques, I’m going to react to last month’s $110.7 million sale of Claude Monet’s “Meules” (Haystacks). It broke the record for an Impressionist work of art, but I think Monet would have been disappointed that the price wasn’t higher!

Although he was penniless as a young artist, eventually his paintings sold at significantly higher prices than his contemporaries’. When his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel exhibited 15 canvases from the Meules series, Camille Pissarro gossiped to his son, “For the moment people want nothing but Monet’s, apparently he can’t paint enough pictures to meet the demand. Worst of all, they all want ‘Meules’…at prices of four, five and six thousand francs.”(1) That would (conservatively) be about $40,000-60,000 in today’s dollars.(2)

In 1890, the year Monet painted this particular canvas, he bought his estate in Giverny (which the family had been renting) for 22,000 francs. By the end of the century, he was getting about 15,000 francs per picture and grossed 227,400 francs annually,(3) which would be about $150,000 per painting and $2.5 million dollars per year. In 1907 he sold a water lilies panel for 45,000 francs, and in 1921 a Japanese collector “handed the artist a check for a million francs” for some of his finest canvases.(4) That’s like $10 million by today’s standards.

In another auction last month, Degas paintings ranged from $3.2 to $8.8 million, one Pissarro fetched just under one million dollars while another went for $6.2MM, and two Cézanne’s went for $2MM and $59.3MM, an enormous sum. The highest Picasso in that sale was $25.2MM, and a Van Gogh brought $40MM, but nothing comes close to Monet’s “Meules.” Other than during the three decades following his death—when his later paintings went out of fashion—Monet got top dollar!

However, $110.7 million is obscene. Lila Cabot Perry, painted the same haystacks under Monet’s tutelage (above), and her version is valued at $5,000 to $10,000.(5) Why is Monet’s worth over 1,000 times more than Perry’s? I think he was the greatest painter in history, but that’s not why. The answer has more to do with the egos of billionaires, who one-up each other to inflate their art investments, rather than the quality of the individual pieces. But, what do I know? My paintings are free!

Monet’s Painting Techniques (and Mine)

There were really two Monet styles loosely delineated around the time of his second wife Alice’s death in 1911. That’s when he began to focus almost exclusively on his gardens and water lilies, which I’ll explore in my next blog piece. But here I’ll mostly describe his earlier techniques and how I use some of them, too.

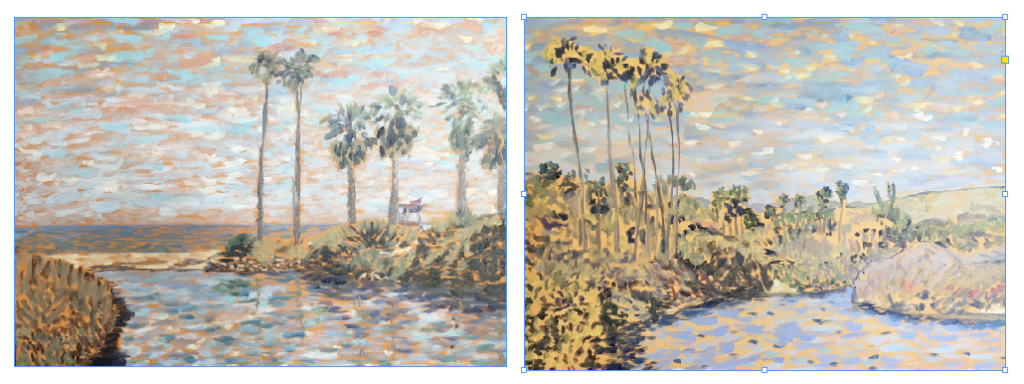

Last month I did two paintings based on these photos (more about this at My Year of Monet #1: “Photography and the 21st Century Impressionist”) from an earlier trip to Santa Barbara:

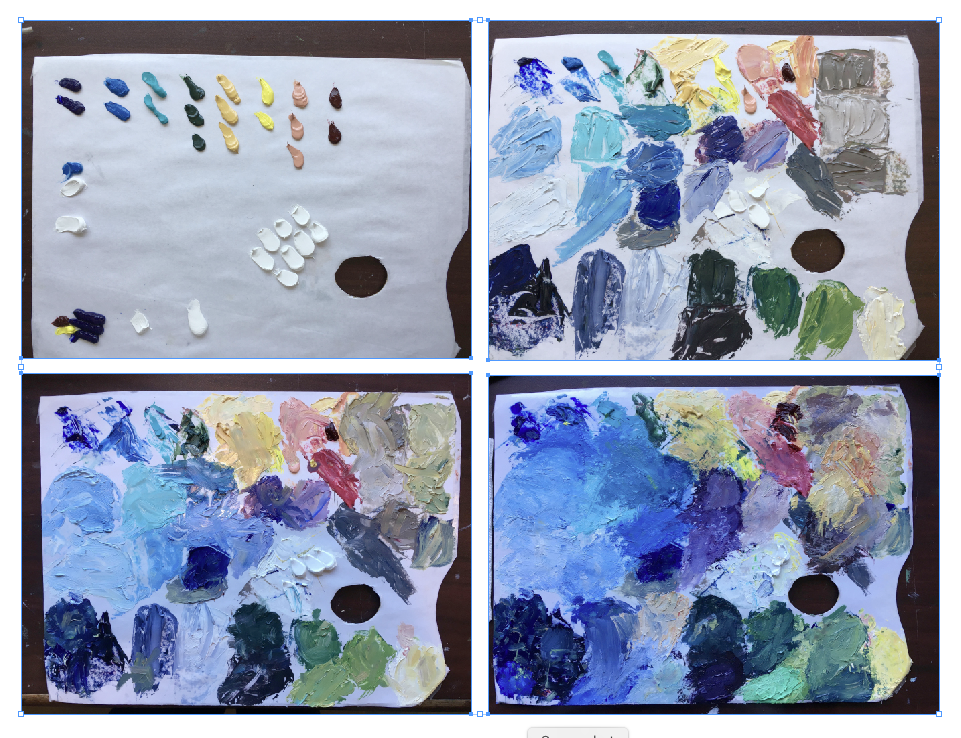

As has been usual for me, in my initial session, I roughed in each canvas with short, disconnected brushstrokes:

Monet did the same. When she studied with him, Lila Cabot Perry observed:

“He brought out a canvas on which he had painted only once; it was covered with strokes about an inch apart and a quarter of an inch thick, out to the very edge of the canvas. Then he took out another one which he had painted twice, the strokes were nearer together and the subject began to emerge more clear.” [6]

Likewise, I built up my canvases with each session:

Monet told Perry,

“When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here is an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you.” [7]

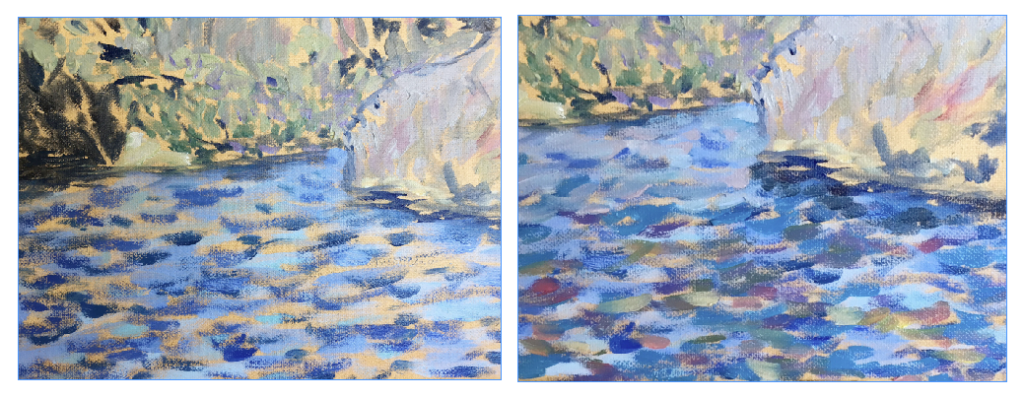

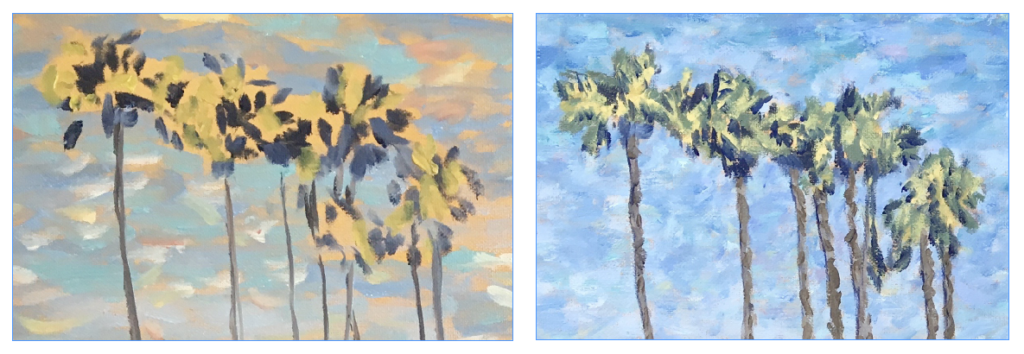

That’s what I try to do! The little streaks of colors shown below eventually morph into Palm trees:

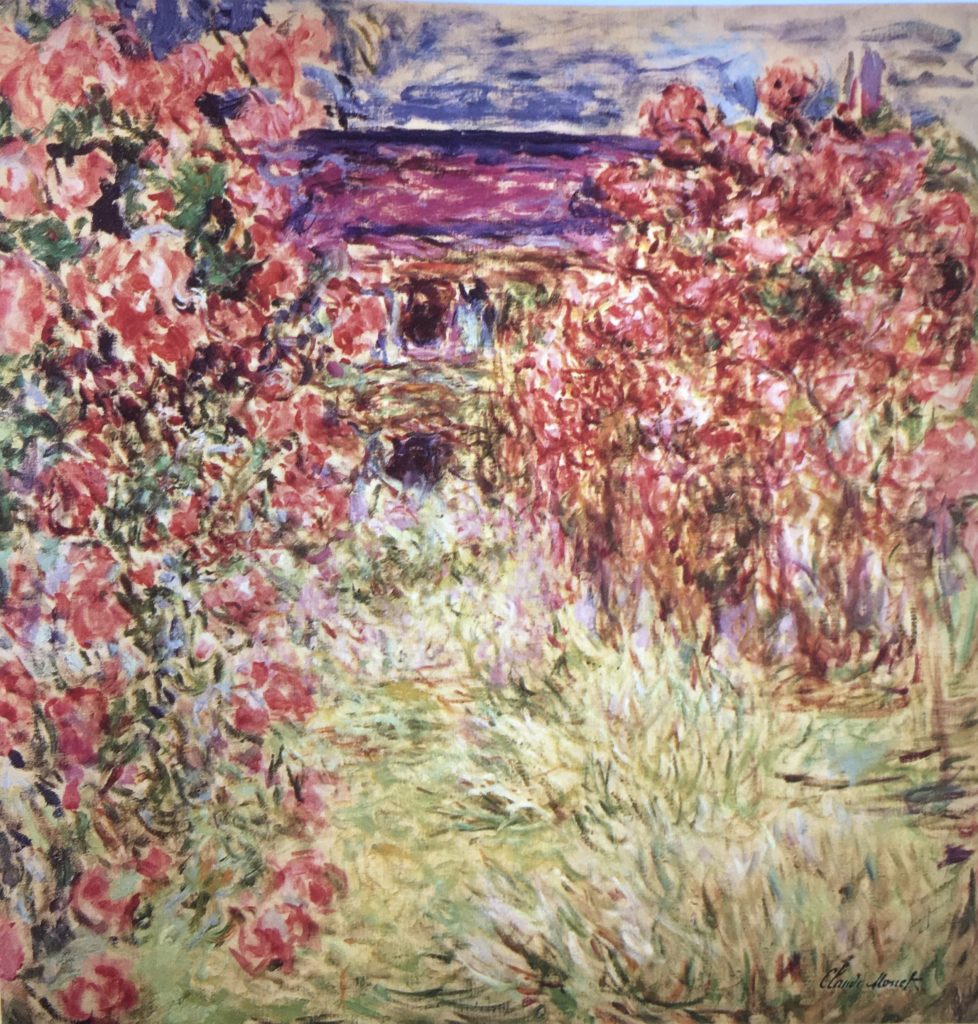

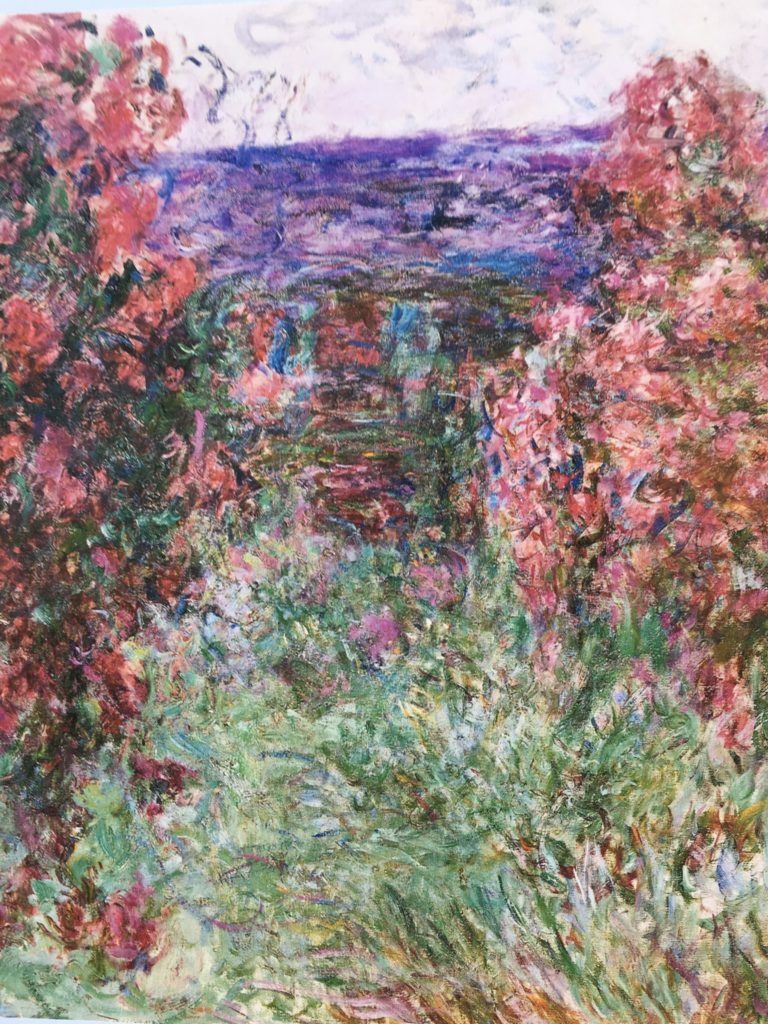

Similarly, Monet’s three incomplete studies of his rose garden and house (below), look like he was gradually building them up. The one on the left appears to have had one or two sessions, the middle one probably more, and the picture on the right is nearly complete:

These were some of his last canvases, probably painted several months before he died in 1926 at the age of 86. They are rare, because Monet usually destroyed canvases that were so incomplete. Easily frustrated and extremely self-critical, he burned, slashed, or stuck his foot through hundreds of paintings.

I can relate to that. Even though I only occasionally throw away canvases, I am dissatisfied with nearly every painting at one point or another. Typically excited after the first two or three sessions, I usually reach a stage where I question whether or not the picture is salvageable. That’s what I was thinking after this session:

I struggled with the hills on the left and didn’t know what to do about that big black area in the center. The background hills on the right weren’t working for me, and the mound on the lower right looked like an infected thumb! If you enlarge the picture, you’ll see what I’m talking about.

However, I’m an optimist and usually believe that I’ll be able to fix what bothers me. Nonetheless, I whine to Lindsey things like, “I don’t think I’ll be able to salvage this one…I’m really struggling with this painting.” Monet could be notoriously grumpy, and when things weren’t going right for him, he would have fits of rage.(8) Despite that, he also maintained an expectation of eventual success with a project.

For the London series in 1901, Monet worked on so many paintings simultaneously that he often couldn’t locate the canvas he wanted before the clouds or fog shifted. He only painted for a few minutes on one picture before switching to another that captured the moment, and the changing weather made him feel exasperated much of the time:

“The fog is back…and the whole day kept changing, picking up one canvas then another, to put them back a moment later. In the end it was enough to drive you crazy, no longer knowing exactly what I was doing…a real spell of bad luck because yesterday I had just settled down when the snow came to the point where I was covered with it and you could no longer see anything.…in any case I’m not losing courage, quite the opposite.” (9)

Monet’s Palette (and Mine)

Monet’s color choices changed over the course of his long career. At one point, he was only using a white, blue, red, and yellow. Another time, he told an aspiring painter that he always used the same eight colors.(10) Detailed analysis by recent scholars have shown other colors on his palette, which I’ll discuss next time.

He usually used a canvas primed with a dull, matte, lead white ground, which helped him to establish the scale of his values.(11) Many of his compositions have unpainted areas, often along the borders or corners. I prefer starting with a bright, earthy, orange undercoat, which adds depth; and, I try to leave pinholes throughout the canvas to let the orange provide a bit of glimmer and continuity.

The Santa Barbara pictures were created with a fairly typical palette for me: two reds, yellows, and blues, plus sometimes a green, purple, or earth tone. I use titanium white, which is today’s equivalent to Monet’s lead white.

I start with my colors in a row on top. When Monet became virtually blind, he arranged the oils on his palette and knew what they were even though he could not differentiate between the colors. If he wanted green, he knew how much yellow and blue to mix, because he’d done it countless times before.

Like Monet, I don’t use black from the tube. In the lower left corner, I mix three primary colors to create a “blackish” and combine that with colors to generate dark tints. I could probably do it with my eyes closed! That “black” area I mentioned previously is actually very dark green, blue, and grey shades.

Finishing the Paintings

Monet returned to his canvases over and over. He shipped many of the London paintings back and forth from Giverny and worked on them repeatedly over a four-year span. He might spend only a few minutes adding brushstrokes before quickly moving on to the next composition. Sometimes he applied wet on wet paint, but he often built up wet on dry layers. By most accounts, he revisited his paintings numerous times and the massive Grand Decorations apparently had hundreds of sessions. Using electron microscopy and other tools, scholars have analyzed various canvases, and this cross section from a 1918-19 “Weeping Willows” revealed nine layers in one small area (12):

Over a two-week period, I spent about 20 hours on the Santa Barbara paintings in a total of seven or eight sessions. Eventually I felt satisfied and signed them. That’s my point of closure.

On the other hand, Monet signed his pictures when they were sold. In many instances, he put the wrong year because he couldn’t clearly remember when they had been painted. After he died in 1926 at the age of 86, his three studios were filled with unsigned paintings. To authenticate them, his son and heir, Michel Monet, stamped his father’s signature on some of the canvases. Sadly, for many of these, he used black paint.

Upcoming in “My Year of Monet #3”

Wait until you hear about my trip to San Francisco for “Monet: The Late Years” and its impact on my paintings! I’ve been experimenting on six canvases (water lilies and gardens) with some of Monet’s favored colors during the final two decades of his life. Believe me, I’m no Monet, and it has definitely not been smooth sailing! I am doubtful that these paintings will survive, and it’s surely no coincidence that Claude would have probably felt the same way. Stay tuned…

References

(1) Gordon, Robert & Forge, Andrew. (1983) Monet. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., p. 169-70

(2) Historicalstatistics.org

(3) Wildenstein, Daniel. (1996) Monet or The Triumph of Impressionism, Taschen edition, p. 274, 341.

(4) King, Ross. (2016) Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies, Bloomsbury, pgs. 243-249.

(5) Invaluable.com

(6) Perry, Lilla Cabot, “Reminiscences of Claude Monet from 1889 to 1909,” The American Magazine of Art, Vol. 18, No. 3 (March, 1927), pp. 119-26.

(7) ibid.

(8) King, op. cit., p. 38.

(9) Gordon, op. cit., p. 186.

(10) Gordon, op. cit., pgs. 266-267.

(11) Barry, Claire M., (2019) “‘Color is My Day-Long Obsession’ Monet’s Late Painting Materials and Techniques, 1914-1926” in Monet: The Late Years, edited by George T. M. Shackelford, Yale University Press, p.36.

(12) Barry op. cit., p. 35.

There is nothing better than walking on Moonlight in the early morning and watching the terns all facing into the wind and puddling around in the shallow surf’s edge. The joy is seeing their reflections in the water as well. Your paintings, while not of terns with their orange beaks, still remind me of early walks where it’s all about the ocean. I love your paintings and the style of strokes. Very nice. Very relaxing to look closely. You are gifted with a passion and talent to go with it. Seeing them is just as joyous as seeing my terns in the surfy watery sand.

Your philosophy of having your artwork displayed is generous and an act of kindness each time gifted. Good for you.

Pam – 5 exits from you

Hi Leigh,

I am late to the party, but wanted to let you know how much fun it is to read about your process of painting and the changes that come along later so that the painting is in effect, always alive and perhaps changing. As a non-painter but a crazy camera person, I have such respect for the hard work that goes into each of your paintings. I often tell my friends that the “camera took the photo, not me,” which is a feeble effort to explain where an image comes from. It is true with the camera, that I often feel that I can’t explain why that particular image was taken, although I was drawn to the subject. Thanks so much for sharing your work with us! Best to you and Lindsey, Mary

Hi Leigh: You are one of the great secrets of Southern California – I like that you paint our local scenes.

I gave one to a former tenant who enjoys it on his living room wall in Moscow, RU. Fondly – Wayne Chapman

Dear Leigh,

Loved learning about Monet and his influence on your paintings. Even more, I loved your explanation for the outrageous prices paid for “fine art” and your disclaimer, “But what do I know,? My paintings are free!” When your paintings start selling for millions, we’ll be glad of that.

Hugs, Cliffwoman (and the big guy)

Hi Leigh,

I admire your dedication to your art. Investigating Monet’s technique must be gratifying.

I’m sorry for you that your paintings don’t sell for $110 million, but I’m happy for me because I can enjoy one of your lovely paintings of the Seine. I recall seeing a lovely Monet at the Getty.

Keep it up and take care my friend.

Dean

Leigh,

Enjoyed reading about your inspiration and how you are incorporating a Master’s techniques into your own works. The journey that you are sharing offers insights to a non-painter that might not (was not!) ever considered.

You have a gift.

Leslie